I bring a deep interest in language, culture, and history to everything I do. From early on, I’ve been drawn to how people make meaning across different worlds — whether through literature, translation, or shared stories. That perspective continues to inform my work today: I value intellectual curiosity, cross-cultural understanding, and the power of communication to bridge divides and build connection.

I was “lost in translation” as an eighteen month old when my family returned to Northampton,

Massachusetts after a year in Jerusalem. I did not know the English word “water”; I only said the Hebrew

“mayim.” My parents translated for the daycare teachers. As a toddler, I did not possess the self-

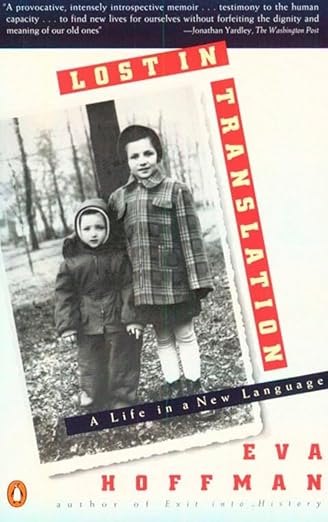

awareness to understand the significance of my experience. Now, years later, after reading Eva

Hoffman’s memoir Lost in Translation (1989), the meaning of that memory is more resonant.

Hoffman’s memoir offers insightful ruminations on immigration, language, and culture from her

perspective as a Polish immigrant to Canada in 1959. Initially, as an adolescent and even as a young

adult, she struggles to express herself in a new language and discovers that some thoughts simply cannot

be translated and are lost. Yet her unique situation also makes her keenly aware of cultural nuances –

nuances, ironically, often lost on others. Cultural relativity becomes her métier; Poland, Canada, and the

United States, her points of reference. Hoffman does not feel the pull of one culture, but of many. “New

York, Warsaw, Tehran, Tokyo, Kabul—they all make claims on our imagination…we are always

simultaneously in the center and on the periphery” (Hoffman 275). As an immigrant and a deft observer

of culture, Hoffman has the ability to recognize the fallacy of absolutism and the truth of pluralism.

Her unique perspective has attuned me to the challenges immigrants face and has intensified my

desire to understand other cultures. After all, being lost in translation relates not only to the literal barrier

of language, but the figurative barrier of culture. Such a barrier exists when one limits herself to her own

immediate experience. A singular frame of reference can be static and dull. Without knowledge and

appreciation of other cultures and of history, I would be confined solely to my own world in the

immediate present. I would be robbed of a medium of translation between one world and another.

My reading, study of foreign languages, and fascination with history have made me aware of the

many forces and dimensions beyond myself. Besides one’s own immediate experience, there are one’s

personal past and one’s imagination. Further, there are the collective historical past and the simultaneous

existence of many cultures. The multifocal cultural lens Hoffman exhibits is one that I have tried to

develop. Studying foreign languages, especially Latin and French, has allowed me to do this. Certain

Latin expressions like adversus solem ne loquitur – “don’t argue against the sun” – do not have adequate

English equivalents. Their meaning is unique to the place and time where they were spoken. Similarly,

history deepens my understanding of cultures not readily accessible. When I read the poetry and

harrowing accounts of the Soviet writer Osip Mandelstam, I am vicariously transported to the harsh

realities of Stalinist Russia, though that world no longer exists. Words and books immortalize the

experiences of people whose stories would otherwise seem distant and unattainable. Their accounts

become my points of reference. I begin to understand the popular wisdom of another time and how a

society should not be subject to repression. As I translate their lives to our day, I derive lessons

concerning ethics and politics. Consequently, I am not lost in translation between different cultures or

periods because I realize that each offers lessons for all others.

The state of being lost in translation need not be permanent. By choosing to value others’

experiences and reflections, I venture into the realm of translation. When my own frame of reference

seems limited, I seek the perspective of another, whether it be Hoffman, a wise Roman, or Mandelstam. I

integrate the thoughts of others so that they inform my own. Only with an array of diverse and insightful

views can I fully understand myself. A translation of self does truly require the world.